Your weekly exploration of art and its mediums. The stories we tell and the ways we tell them.

A collection of things I've seen, this weeks story I first saw in my school’s library and became engrossed by the man behind it.

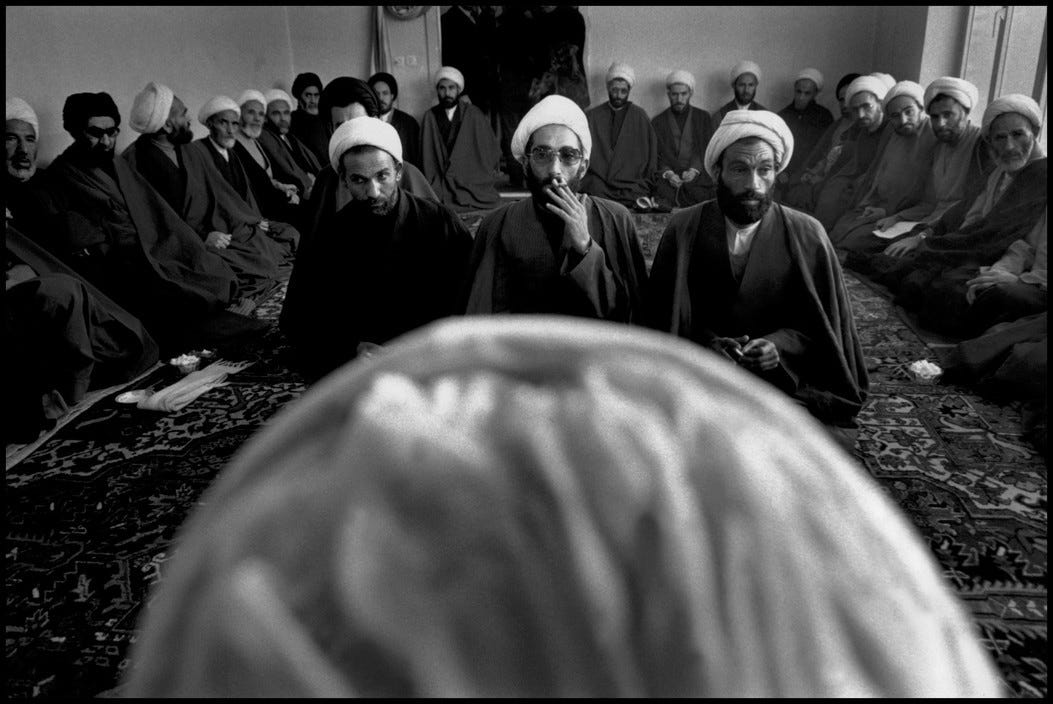

Clergy present grievances to Revolutionary government. Azerbaijan. 1979. © Gilles Peress | Magnum Photos

I became almost obsessed with Gilles Peress and his work during a class assignment that introduced me to his book, Telex Iran: In the Name of Revolution. It is a personal documentation during a five-week period in 1979-1980 while the American Embassy was seized in Tehran and hostages were being taken. His photos are accompanied only by Telex messages that he and his editors in Paris were exchanged.

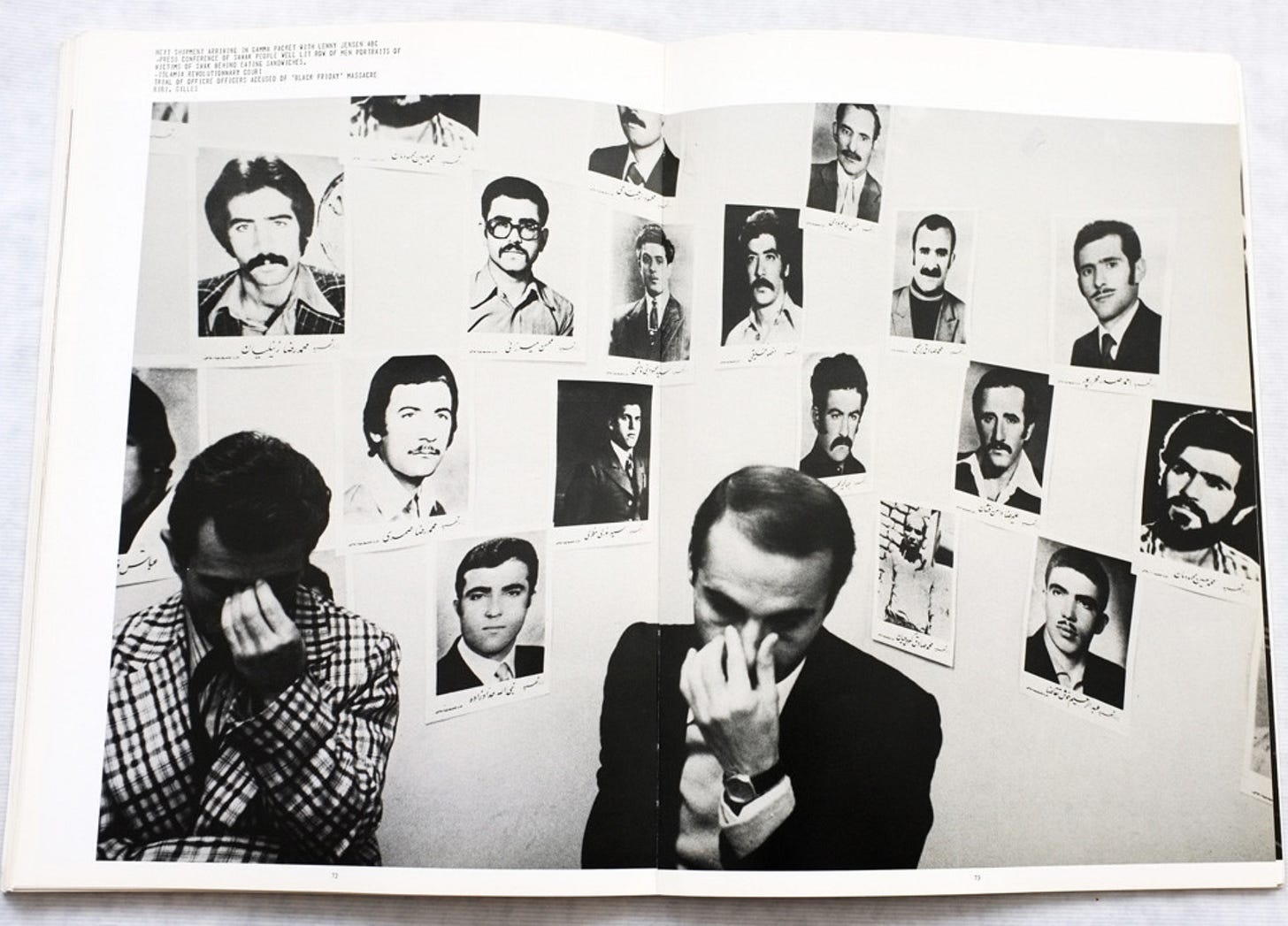

Savak agents on trial at Evin prison. Tehran, Iran. 1979. © Gilles Peress | Magnum Photos

The telex messages often have nothing to do with the photo that it accompanies. In them Peress asks what his colleagues in Paris are having for lunch or he will tell them that a caption is wrong under one of his photos. There is one where Peress asks to come home and he is denied by a colleague who says that there are rumors of something big going to happen in Iran and he needs to be there if/when it does.

There are two narratives happening simultaneously in the book and while I read the messages and looked at the photos the book became loud. As if I could hear the voices in the short exchanges and the commotion of the photos. The book and also Peress’ work in general is him trying to understand and decipher what he is being a witness to and also his individual relation to it.

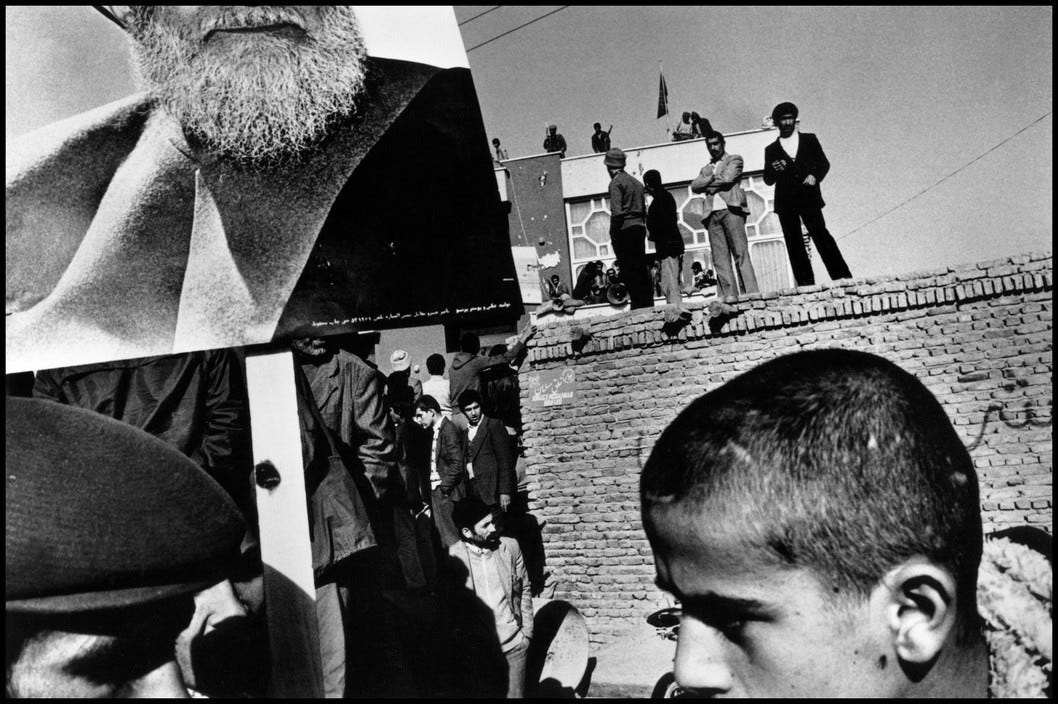

Demonstration in favor of the leading opposition figure Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari. Tabriz, Iran.1980. © Gilles Peress | Magnum Photos

In an interview with the Institute of International Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, Peress says that he became “extremely suspicious” of language after starting to realize that there was a huge gap between language and reality. When we talk to the collective about anything, the political and intellectual language is disconnected from the reality of the subject. Somewhere along the line language became a substitute for engaging with reality instead of a tool for changing it. He says that he “needed a vehicle to understand and formalize what was out there in the world,” something other than language to mediate his relationship with reality.

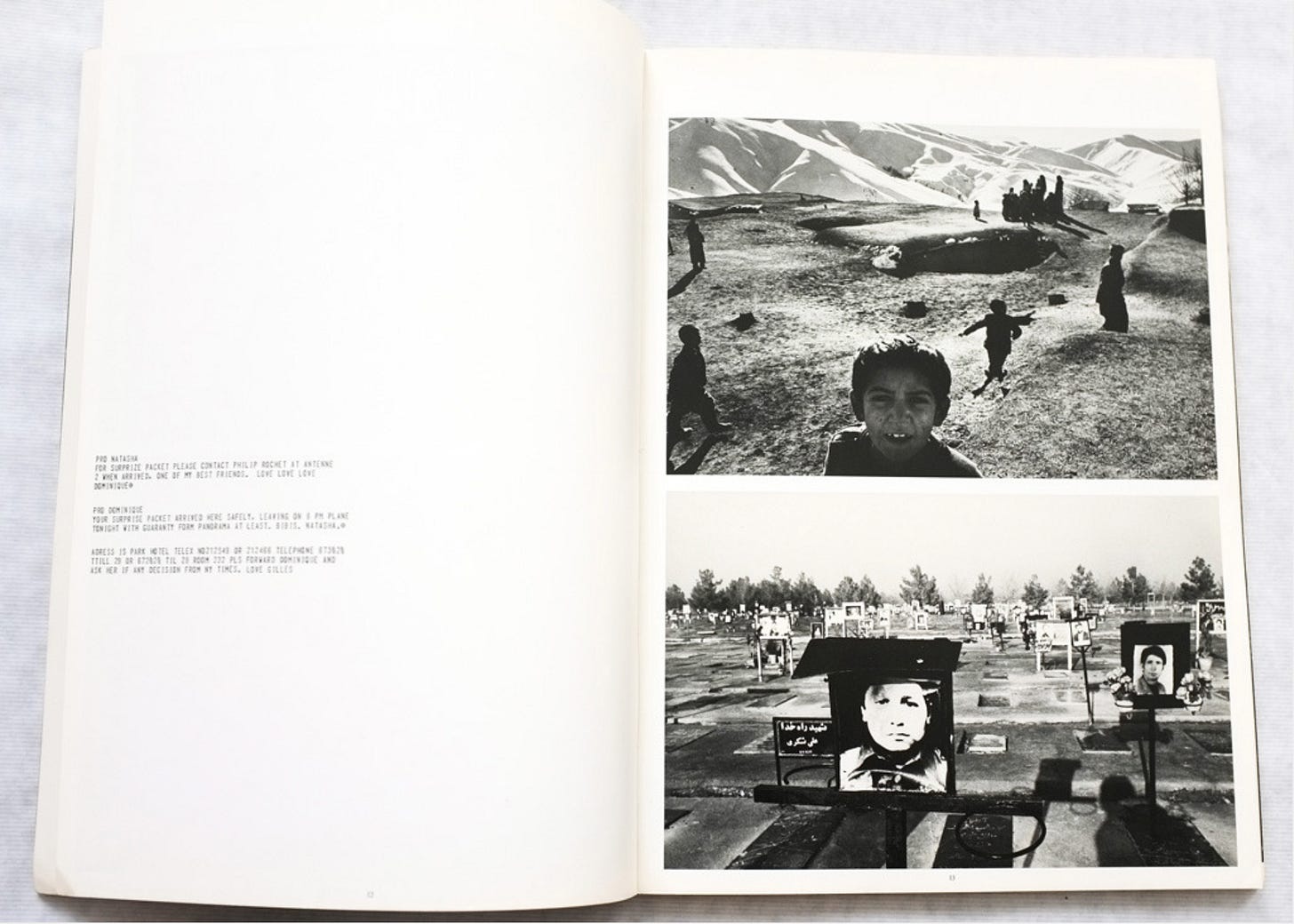

Demonstration in a stadium. Tabriz, Iran. 1979. © Gilles Peress | Magnum Photos

In the photos we see him, something that photojournalists during this time were adamant about not doing. When attempting to document history it is custom in journalism, and at this point expected, that you remove yourself from the photo for objectivity. However, Peress inserts himself in them by making it clear that there is someone behind the camera. In an interview he says that he would even take a photo of a glass of water he was drinking if he felt it was important.

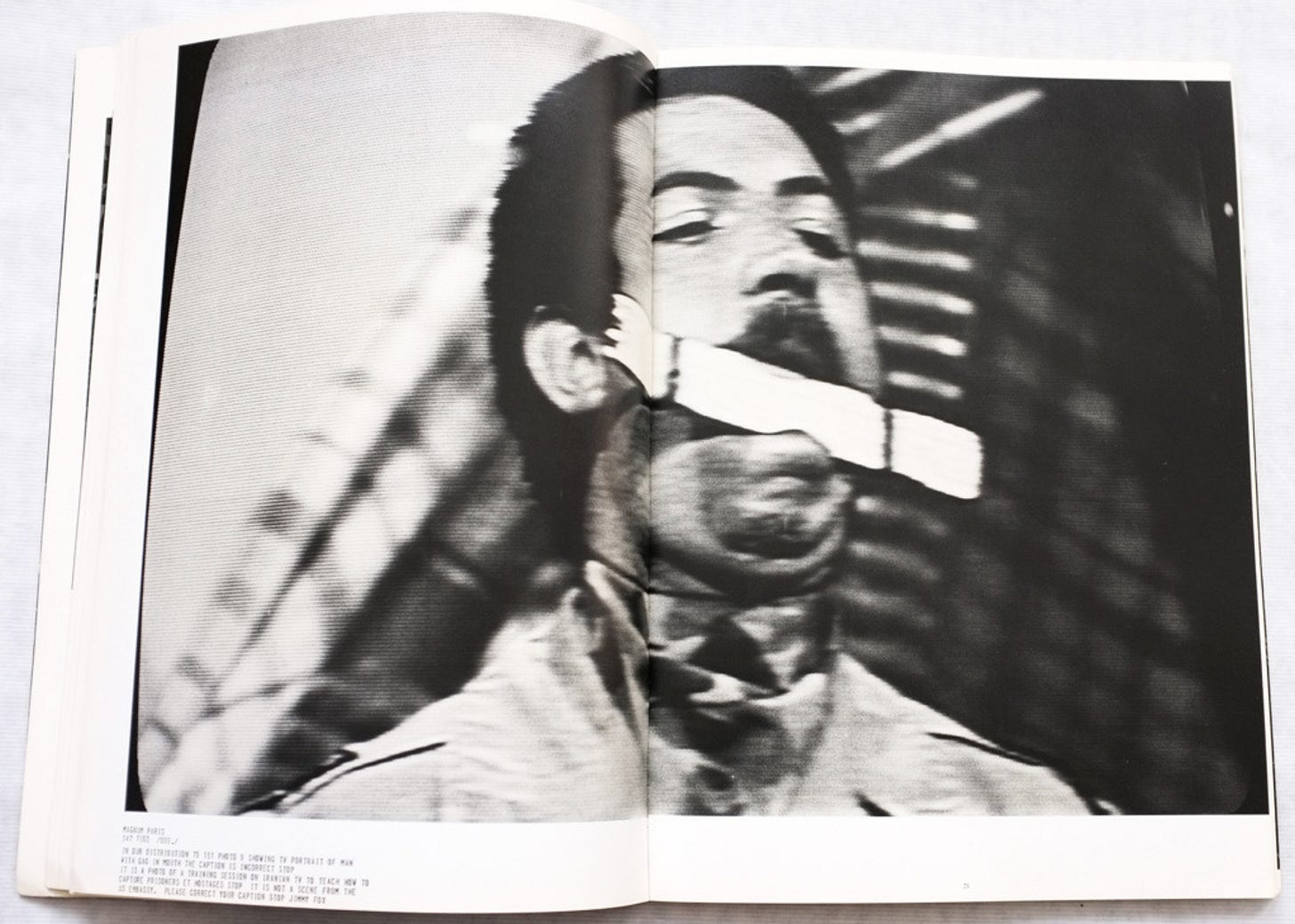

A page from Telex: Iran, 1983, Gilles Peress

Peress’ work does little to help you understand the culture, place, or event it shows you how far away you are from understanding it. The puzzling nature of the photos exaggerate the distance we have to reality and Peress works to show this mystification of history and its atrocities. In the interview he describes, what he calls, the curse of history. “You are damned if you remember and damned if you don’t.” The repetition of history isn’t in whether or not we remember it but rather in whether or not we understand it.

Television program on military training. Taking a hostage. 1979, Gilles Peress.

Peress says that his photographs are where his language finishes and where the audiences begins and that half of the text of a photo is in the reader who is forced to have an internal dialogue with the work. He has said that a photo has four authors, the photographer, the camera, the viewer, and reality. But it is reality that speaks the loudest.

Be well, Readers.

For more information: